AS MIDWINTER APPROACHES and the nights draw in, it’s time to sit comfortably and contemplate the passing year.

INSTEAD THIS YEAR I decided to paint and decorate our flat for the first time in a decade. The process of clearing, cleaning and repairing set me thinking about ghost stories and the cycle of loss and renewal at year’s end.

It started by my wanting to freshen up the bathroom which had gone a bit mouldy around the edges and continued into my children’s bedroom, which I had been gradually taking over as my own. Both my children have well and truly flown, one to Canada and one to Spain, travellers like their parents. But after a visit from my boys in October – the first time we had all been together in two years – the usual cycle of visiting and goodbyes left me feeling bereft. EMPTY NEST the casual term to describe the bafflement of mother and father bird suddenly finding themselves alone, didn’t quite cover the wave of existential nostalgia and grief, that I felt. It was as if my heart had caught up with my head, woken to the obvious fact that the direction of travel of my children was away. The coats I kept by the door, the clothes in the cupboard, the guitar racks on the wall no longer had a function. Our quirky, slightly overstuffed family home for four had morphed into a museum for two.

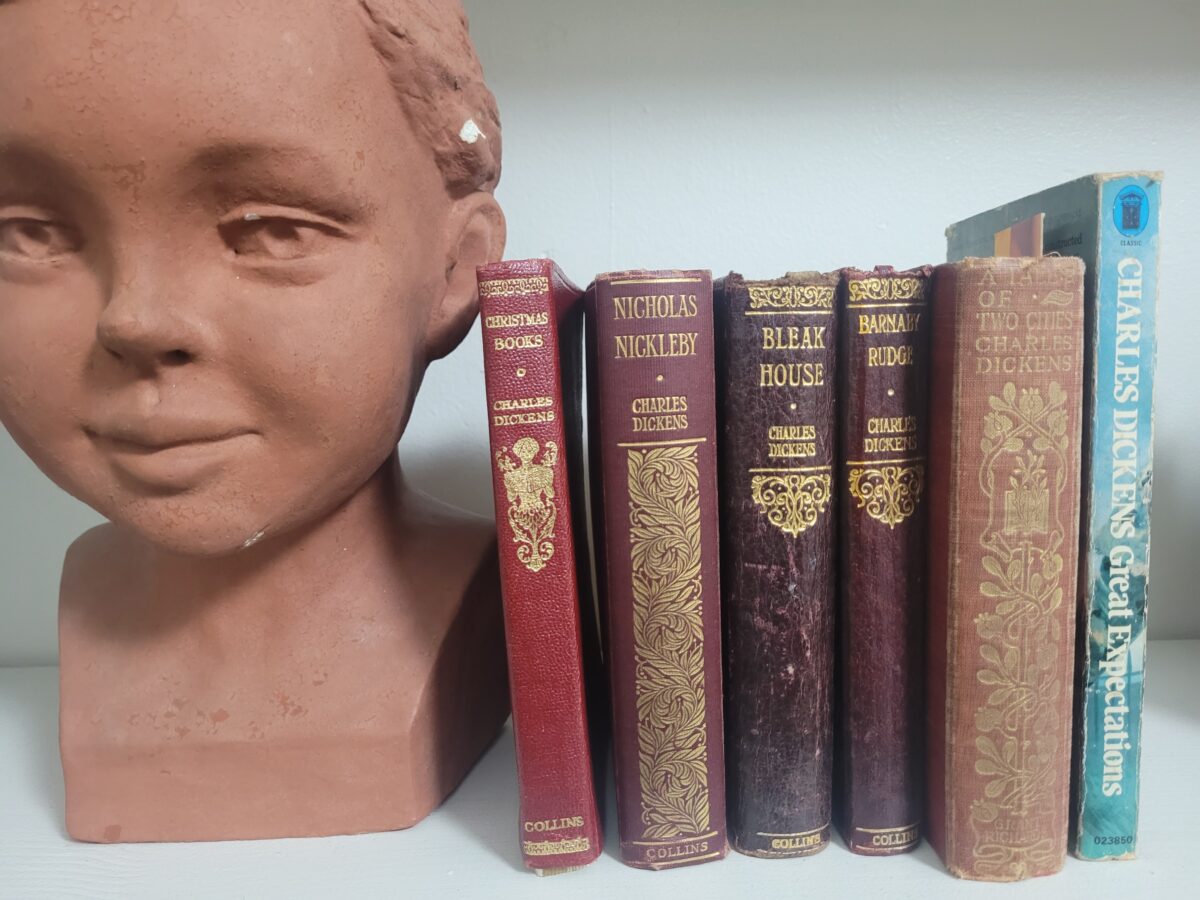

As I emptied the rooms to paint, the flat’s good Victorian bones were revealed, but also the decay I had been avoiding for years – moth in the corners, dinged skirting, holes in the wall. Ancient coal dust (yes coal dust) behind the shutters. My eyes were opened to decay throughout the flat – the cobwebs hanging high on the ceiling – which Google tells me are each a home for long dead spiders – spurred me on. Our flat reminded me of Miss Havisham’s room where, to quote Great Expectations, “everything … had stopped, like the watch and the clock, a long time ago.”

But the uneasy fact is that time never stops. To paraphrase the second law of thermodynamics, a concept that emerged in the early 19th century from the observation of steam engines – the overall disorder (entropy) of the universe, as a whole system, is constantly increasing. The direction of spontaneous processes, commonly referred to as the “arrow of time” goes in only one direction eg. that broken cup on the floor is not going to leap up and mend itself.

Working in my now intentionally deconstructed house, I was alert to the entropy that had been progressing unseen for years. It was startling and a little dark to realise that the small box of pebbles in a drawer, my mother’s broken necklace, the photograph of my twin sister, all intensely valued artefacts, were well on their way to becoming silt. Larger items of furniture many inherited as parents died or downsized felt oddly transitional –were they permanent or just passing through? I remember coveting these things in an earlier time when I owned little and craved a more ‘grown-up’ house. With age I begin to see that I don’t really ‘own’ these things, that stolid and impenetrable they have a life of their own, and will probably outlast me. In fanciful moments I think that my possessions, like the furniture in Guy de Maupassant’s short story Qui sait, could take flight and go for a walk in the moonlight:

I presently distinguished an extraordinary shuffling and stamping of feet on the staircase, on the floors, on the carpets; a sound not only of boots and’ human shoes, but tapping of crutches, of crutches of wood, and knocking of iron crutches which clanged like cymbals. And behold, I perceived, all at once, on the door sill, an armchair, my large reading chair, which came waddling out. Right into the garden it went, followed by others, the chairs of my drawing room, then the comfortable settee, crawling like crocodiles on their short legs; next, all my chairs bounding like goats,and the small footstools which followed like rabbits.

Perhaps my things will go to live somewhere else and let me live quietly but I doubt it. Lying in bed at night looking at the cobwebs, objects become harbingers, telling me that it is I, not them, at the entropic centre, and like Miss Havisham I am in danger of haunting my own house.

Old Marley was dead as a doornail

In midwinter I am drawn to the books of Charles Dickens, in particular, A Christmas Carol. It is a story that my mother read to us as children and that I in turn read to my own children. Each successive generation intrigued by the ghost story but confused by the Victorian language waited to grow up and read it for themselves, which I do every year.

As a harbinger of bad karma and missed opportunities you can do no better than Jacob Marley’s ghost, the first terrifying vision that opens the story of Scrooge’ s encounter with his own life. Marley’s visitation of Scrooge, is both generous and selfish and full of despair. Haunted by the shortcomings of his own life he wishes to set things in order, spare his old friend a similar fate. But there is something disingenuous about Marley – it is unclear what is driving him. Is he a (dis) embodied conscience from God? A product of Scrooge’s imagination or even indigestion (“there is more of gravy than grave about you”). How is this form of ghostly housekeeping all going to work out? It is never clear whether Scrooge has had an encounter with the supernatural or just a particularly bad dream. And in the end, A Christmas Carol emanating from the darkness of midwinter allows us to consider that both possibilities are true.

_______________________________________________________________________

When I walk into this house where I have lived for over 30 years, it feels unfamiliar, like the first time I walked in. In the bedroom I start at the top of the bookcase, 13 feet up where the cobwebs create a bridge to the paintings hanging around the top of the wall.

I float downwards. Excavating. Children’s books, boxes of photographs, letters bound with string. The ancient handwriting hieroglyphs tell me who, what, where, and how long ago. Books and more books. I open, close, stack things on the floor.

The first flood of memory is pure delight, stops me in my tracks. I sit and read letters, put tiny beads in tiny glass jars. Rake my fingers through disintegrating paper, metal, glass – remembering, trawling. I am lit up like Scrooge at Fezziwig’s Christmas Ball.

Is it deadweight or faerie dust? Should I keep or release? To the recycle centre, to the charity shop? I realise that the far-gone things are the most important. There is no half-way house, they will either be kept or condemned to landfill. The Ghosts of Christmas Past and Present are in the room. They smell of holly and roast lamb but there are starving children hiding nearby. I glory in all the good things but feel warned not to take it for granted.

______________________________________________________________________________

My triage of objects is also a fudge. There are limits. Some things – baby pictures – will have to be boxed and dealt with later. I simply do not have the emotional space.

I feel buoyed up by the lightness and cleanness of our new flat, sensing at the same time that no long-term efficiencies have really been made. As predicted by the second law of thermodynamics the best I can hope for is to maintain a system that is ultimately doomed to fail. Realising this gives me a sense of freedom.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Memory is a conduit that connects what I see, read, try to learn. I come back to materials, this time in my studio where I want to forget and simply work; The engine of memory hums in the background. What floats through the air, what settles around my chair, rises up waiting to be released, to work its magic.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“And then let any man explain to me, if he can, how it happened that Scrooge, having his key in the lock of the door, saw in the knocker, without its undergoing any intermediate process of change–not a knocker, but Marley’s face.

Marley’s face. It was not in impenetrable shadow, as the other objects in the yard were, but had a dismal light about it, like a bad lobster in a dark cellar. It was not angry or ferocious, but looked at Scrooge as Marley used to look: with ghostly spectacles turned up on its ghostly forehead. The hair was curiously stirred, as if by breath of hot air; and, though the eyes were wide open, they were perfectly motionless. That, and its livid colour, made it horrible; but its horror seemed to be in spite of the face, and beyond its control, rather than a part of its own expression.”

A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens